Like most guitar players, you probably stumbled upon the classic 12-bar blues at some point, using exactly the same chord shapes for each part of the scheme. You probably did not know, but there's a surprising number of ways to spice up your 12-bar blues. Ahead, we are going to show you three tricks that are sure to bring verve and color into your 12-bars.

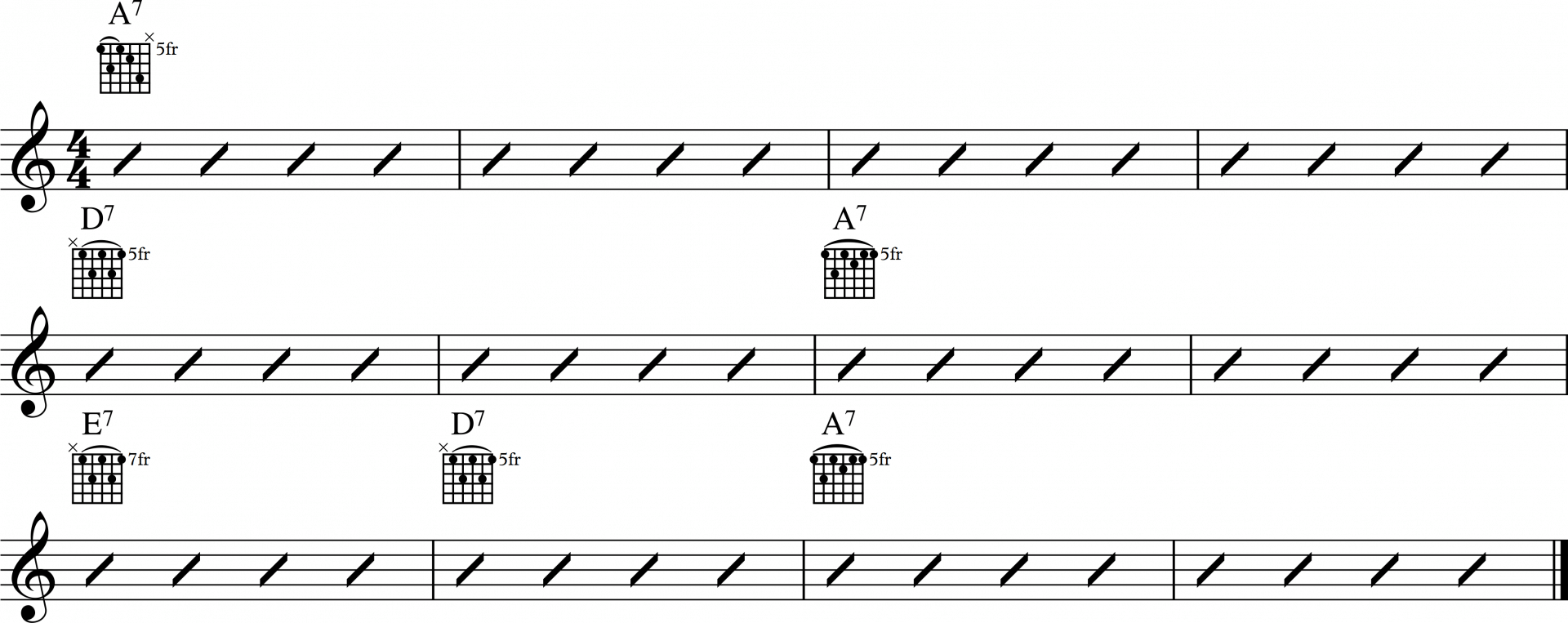

Just to remind you, the above is a quick overview of the classic 12-bar blues scheme. It is based on three chords of a given key, the tonic (I), the subdominant (IV) and the dominant (V). A chord progression based on the intervals IV V I is also known as a classical cadence. We are going to play a blues in A, so the chords we use are A7 (I), D7 (IV) and E7 (V)

The Dominant 7th Chord

The dominant 7th chord is the main ingredient for all blues arrangements, we can use it for each and every chord of the twelve bars. Using the three or more chords of the same type or quality regardless of its tonal functionality is also known as constant structure.

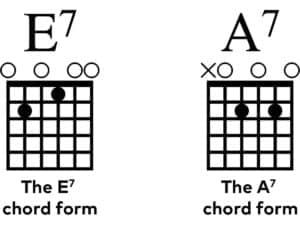

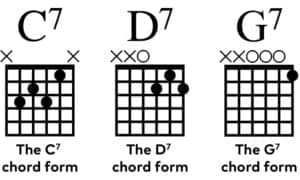

Although the dominant 7th chord is important, most guitar players only know two specific chord forms that they shift across the fretboard:

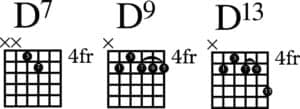

The simplest way to pimp your blues sound is to mix in other chord forms. All chord forms are movable shapes, so we can just shift them around like the E and A chord form. All chords still consist of the same notes, but they will appear on different strings and in different octaves, which makes the sound more varied and interesting:

Sometimes Less is More

As you probably know, basic chords can be defined by three notes, the so-called triad. typically, a triad consists of its root, its third and its fifth. Thus, the C major triad consists of the notes C, E and G. These three notes give the chord its tonal color. So there must be four notes in tetrachords such as the dominant 7th, right? Absolutely correct, but exceptions confirm the rule.

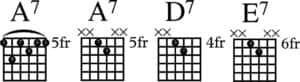

Take a look at the A7 chord above. It is a regular A7 barre chord on the 5th fret. Now we remove the root note (1) as well as the fifth (5). The root note will be played by the bass guitar anyways and the fifth does not carry relevant tonal information. The two remaining notes, the major third (3) and the dominant 7th (7) form an interval called tritonus (it's actually a diminished 5th interval) also known as Diabolus in Musica. As the name suggests, the interval does not sound too pretty if played by itself. It's the part of any dominant chord that demands resolution and gives the chord its urgent, unfinished nature.

Now watch what happens if we shift this interval down one fret. Although the interval by itself stays the same, we can interpret it as the major third (3) and the dominant 7th (7) of a D7 chord, just the chord we need to continue our blues in A. Once again, we cut it right down to a major 3rd and dominant 7th. If we shift the interval to the 6th fret, we get a two-note version of the E7.

So you see, we can play an entire blues with an interval that does not sound too pretty by itself, but which creates a great atmosphere together with other instruments such a bass guitar.

Sometimes More is More

You've learned know that it's possible to cut a blues accompaniment down to a single two-note diminished 5th interval called tritonus, which is part of every dominant 7th chord. Now we'll think about making things more interesting by adding additional notes to chords, rather than subtracting them.

Music theory tells us that all dominant chords belong to the same family, so we can modify them by adding additional tones without losing any of its essential character. The most common way is to add a 9th or a 13th to a dominant 7th chord.

If we take the two-note version of the D7, for example, we can just add the root (1), the 9th (9) and the 5th (5) to magically transform the D7 into a D9. It may sound different, but from a theoretical perspective, it's still performing the same job.

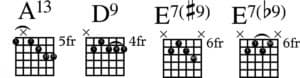

Taking this idea forward, it means that you can take any dominant 7th chord instead of a regular 7th to create a different tone color. Try the following:

It's an A13 chord moving to a D9 and a E7#9 or E7b9. Awesome, isn't it? You can also add a little bit more spice to any chord by sliding into it from a fret above or below, all it takes is a little bit of practice. Just be sure to play the #9 or b9 only over the last of the 12 bars in order to avoid dirty looks from the rest of the band.

Our app Fretello also comes with a large number of backing tracks. Just download it from the app store and try out your new shiny tricks. Also, you play to the backing track below.